History of Mariensztat Square

The history of Mariensztat is that of a road – a ravine, which connected the historic Krakowskie Przedmieście and the Vistula river as early as in the Middle Ages. From the mid-18th century till its end, it was the main road of an iurisdictio (an enclave not subject to the city authorities) established by Eustachy Potocki (general of the artillery in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania) and his wife Maria (hence “Mariensztat”, from German “Mary’s Town”). The fate of Mariensztat was eventually decided by two large constructions.

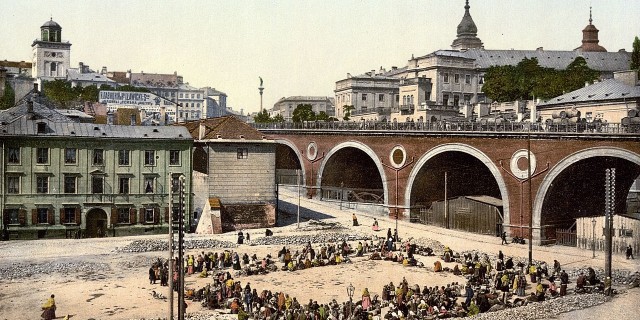

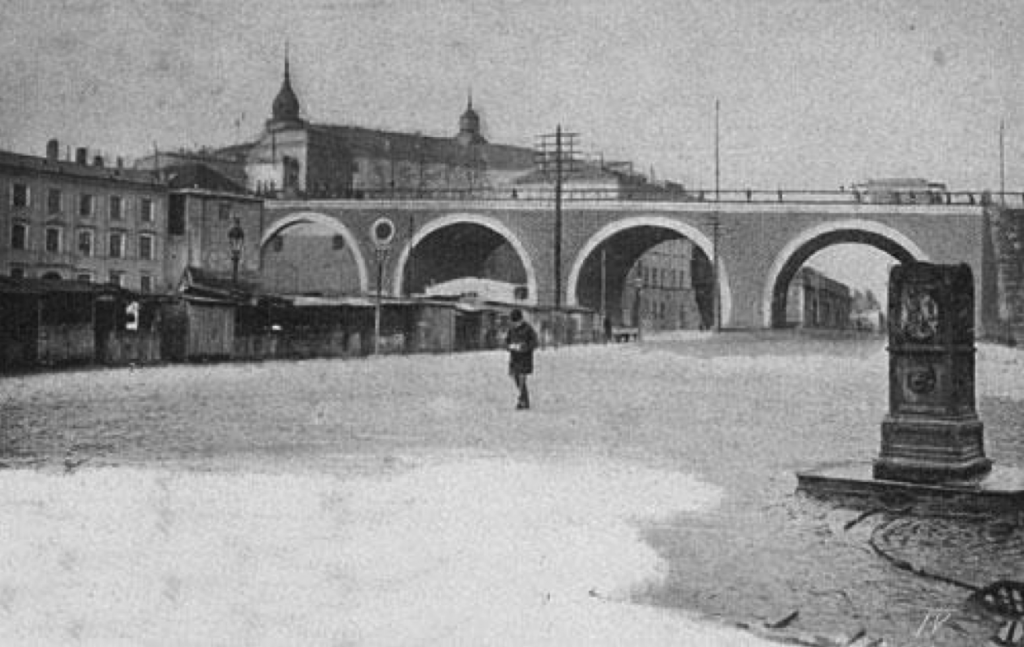

In 1846, the construction of Nowy Zjazd was finished. The street was also known as the Pancer Viaduct and was supposed to lead to the new bridge across the river (the Kierbedź Bridge, completed in 1864). The construction of the viaduct involved tearing down a lot of previously existing buildings in the vicinity of Castle Square, including St. Clare’s Church and the Bernardine Convent; this opened a view corridor towards Mariensztat. Mariensztat’s axis was close to the mouth of Nowy Zjazd, which considerably enhanced traffic in the neighborhood. To improve the flow of traffic, the mouth of Krakowskie Przedmieście was widened in 1860.

Mariensztat Market Square and the Pancer Viaduct in 1913

The Square

After 1843, the city magistrate bought several land plots and buildings, creating a small market square (it occupied the south-eastern quarter of today’s Mariensztat Market Square). The square was filled with wooden stalls, and the primary commodity was food.

In 1913, Warsaw’s oldest market was moved from Old Town Market Place to Mariensztat, which became the main marketplace in Powiśle (and remained so until 1944).

Between WWI and WWII, the marketplace was in bloom; next to the wooden stalls, a metal pavilion was constructed.

Main functions and activities

Mariensztat was the main center of food, sand and wood trade. There were also two steam baths, a printer, a restaurant, several small taverns and tea houses that catered to the needs of vendors, as well as many little stores.

In the early 20th century, a few tall townhouses were built in Mariensztat Market Square. The arcades under Nowy Zjazd were used as storage rooms for theater props and decorations.

Just before World War II, Mariensztat and the whole Powiśle quarter were quite run-down and pauperized, populated mainly by poor people.

Although in 1939 Mariensztat managed to avoid much damage, in 1944 it was almost totally destroyed.

After the War – Labor Heroes’ Neighborhood

The Warsaw Uprising brought down huge losses to the buildings in Mariensztat (many townhouses that could have been rebuilt were demolished after the war, though). In 1948-1949, the present Mariensztat was constructed according to the design by Zygmunt Stępiński and Józef Sigalin. It was the first new residential neighborhood in post-war Warsaw. The complex was commissioned together with a new thoroughfare (Trasa W-Z, East-West Route) on 22nd July 1949.

People celebrating the opening of Trasa W-Z (which connected both sides of the Vistula river) – 22nd July 1949

Urban plan – in search of the “ideal town”

Mariensztat’s urban plan is modeled after Polish architecture of the 18th century, designed to bring connotations with provincial baroque or renaissance. It is supposed to look like a typical small town in Old Poland. In a certain way, it is an attempt to create the “ideal town”: with a market square, green areas, necessary services and facilities, as well as a kindergarten. The heart of Mariensztat is the market square surrounded by townhouses on three sides. The fourth side of the square is open, offering the view of a prestigious success of socialism: Trasa W-Z. It was a common approach of socialist urban planning, where large thoroughfares were eagerly exposed to the public eye. Mariensztat’s main street is Ulica Bednarska. Altogether, 53 townhouses were built in the neighborhood. Top-notch decorations catch the eye – a mosaic with a clock, sgraffiti (paintings on houses’ walls), a social realist scultpure of a tradeswoman. An interesting building is “Waweliowiec” in Ulica Bednarska, which brings intentional connotations with the Wawel Castle’s inner yard.

The neighborhood was constructed in the spirit of “socialist competition” – e.g. the townhouse at Ulica Mariensztat 19 was built in 19 days!

The apartments were very small, but in the largely destroyed post-war Warsaw they were a dream of every Varsovian. The quick pace of construction and problems with the ground the townhouses were constructed upon has made the buildings gradually decay.

Mariensztat became the capital city’s salon. In its infant years, the neighborhood was heavily promoted by the socialist authorities. It was an extremely fashionable place, festivals and dancing parties took place there. Mariensztat served as a setting for propaganda and feature films (e.g. Leonard Buczkowski’s Adventure in Mariensztat), it was also the subject of poems and songs.

The Illustrated Guidebook to the Capital of 1953 reported:

“In summer time, this beautiful square hosts frequent concerts, markets and festivals, which draw thousands of Warsaw residents.”

It is difficult to tell when Mariensztat Market Square started falling into desolation. In the issue of Stolica from 1968, we read:

“Now we no longer care because there is nothing to care about. Our Mariensztat has grown old. It has become forgotten. That’s it, period. (…) The empty Mariensztat Market Square, in which nothing has been going on for years. A new marketplace has been finally opened in the square, but as of yet, a large sign with the marketplace’s rules and regulations seems to dominate over four humble flower-stalls. (…) In the once-adorable “Czytelnik” café, there is now a Food Industry Laboratory, safely locked behind barred windows. Sleepy stores struggle to carry out their monthly sales plans (…). Parking lots with far too many empty spaces. At the fountain – stone boys with cracked noses, a clock that has long forgotten how to chime.”

On 12th August 2009, the urban plan of Mariensztat was introduced into the Polish heritage register (by the decision of the Mazowsze Voivodship Heritage Conservator), due to its uniqueness and exceptional “small town feel”.